There are few places on Earth more depressing than an abandoned asylum. But leave it to the entrepreneurs of the paranormal tourist industry to take that raw, industrial-strength sadness, slap on some discount Halloween decorations, jack up the price tag, and call it a “VIP overnight experience.”

That’s how I found myself at Ashwood Institute for the Criminally Insane, where for the low, low price of $699.99 — plus a $149.95 “psychic protection surcharge” — I was given the opportunity to stumble around in the dark, breathing in seventy-year-old asbestos, while pretending that faint breezes and crumbling plaster were angry spirits of the damned.

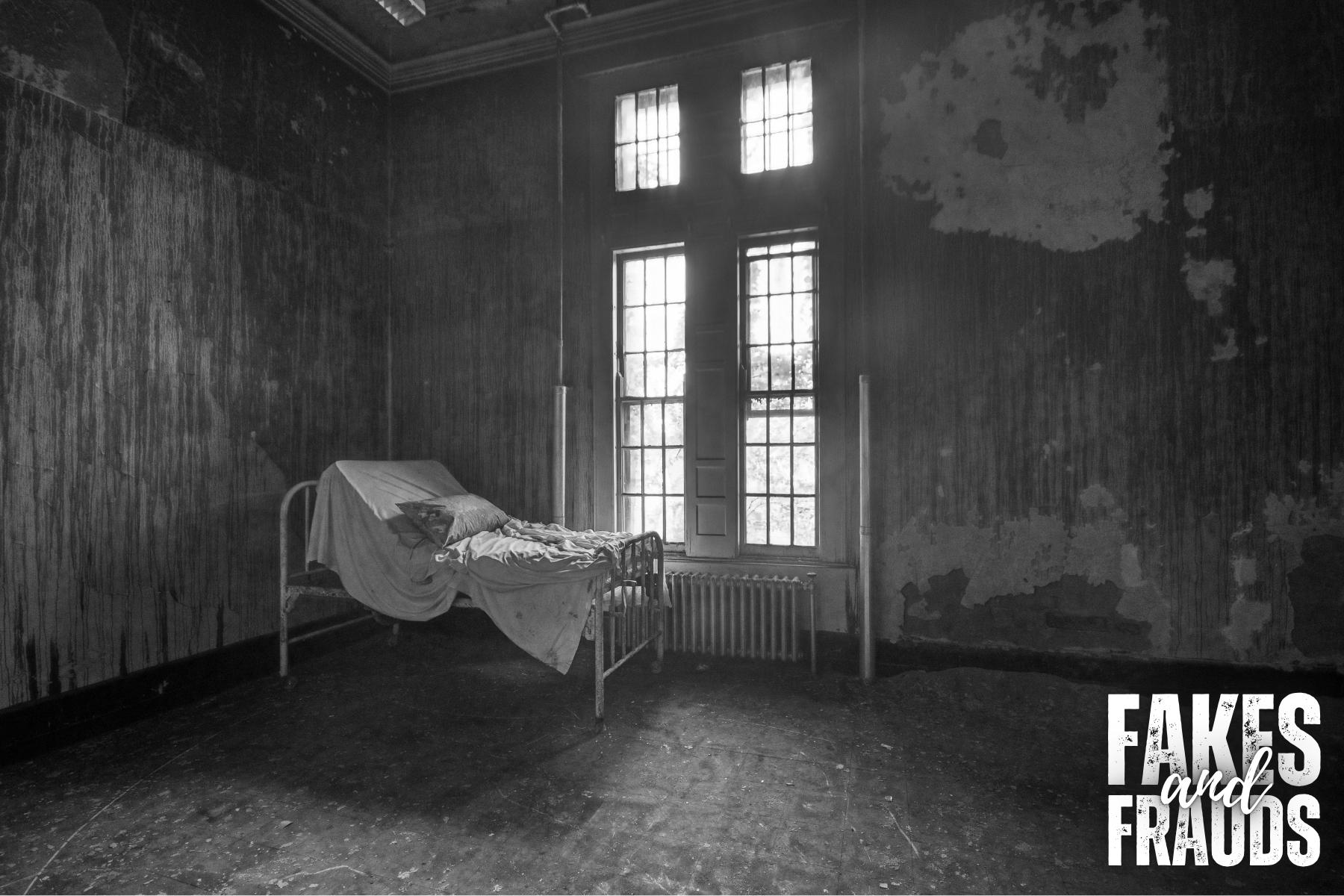

Built in 1891, abandoned in 1973, and rotting steadily ever since, Ashwood sits at the edge of town like a middle finger to both history and basic structural integrity. Every window is shattered, every hallway is sagging like an old drunk at closing time, and every square inch is covered in graffiti ranging from the expected “666” scribbles to surprisingly poignant messages like “Becky was here.” According to the staff — a group of middle-aged goths and disillusioned high school theater kids — this graffiti is “evidence of spiritual activity,” which is about as convincing as arguing that crop circles are proof of intelligent alien life after a fraternity party.

Upon arrival, we were each handed an EMF meter the size of a key fob, a tiny flashlight that barely illuminated the despair on our own faces, and a waiver acknowledging that Ashwood is not responsible for “paranormal injury or psychological distress.” I would argue they should be sued for crimes against common sense.

The tour guide, who introduced himself as “Damien Darkmoor” — no, really — led us through a series of “hotspots” carefully curated for maximum melodrama. The Solitary Wing. The Hydrotherapy Room. The Shock Therapy Theater. Each more dilapidated and less atmospheric than the last.

Every flicker of our flashlights, every gust of wind through the broken windows, was solemnly interpreted as “aggressive spirit activity.” Someone’s meter beeped near a rusted pipe, and Damien nodded sagely, as if the spirit of a lobotomized 1920s bootlegger had just given us a thumbs-up from beyond the grave.

The grand finale, the “VIP Private Investigation,” involved splitting into groups and wandering the halls alone, except for the strategically placed Bluetooth speakers that periodically belched out prerecorded sobs, screams, and, at one point, what I swear was the Wilhelm Scream from a Warner Bros. sound effects library. Ghosts are apparently big fans of public domain stock audio.

One woman in our group, armed with a K2 meter and the unshakable conviction that ghosts communicate primarily through flickering LEDs, spent twenty minutes interrogating a damp mop leaning against the wall, convinced it was a spectral inmate named “Elijah.” No one corrected her. Correction implies hope.

By the end of the night, my psychic protection remained unchallenged, my sanity remained intact, and my patience for humanity’s incurable gullibility had eroded another three percent. I saw no spirits. I heard no tormented voices, unless you count the grumbling of my own stomach as I regretted not smuggling in a snack.

Ashwood Institute is not haunted by tortured souls. It’s haunted by a far sadder truth: that in a world filled with scientific marvels, technological wonders, and genuine historical mysteries, people will still pay three hundred bucks to wander through condemned buildings and convince themselves that every cold draft is a message from the beyond.

The only real danger at Ashwood isn’t spiritual possession. It’s the slow, steady drain on your bank account.